Damn. Prepare to say this over and over as you read this book.

I don’t think I’ve ever read a book where I involuntarily said damn out loud so many times and with so many different intonations. There were plenty of “Daaaaamns,” as in “Oh, yeah. That’s bad. We’re screwed,” but also a number of “Damns!” and “Damnity damns!” along the lines of “That’s mind-blowing!”

But before we dive into all the damns, a bit of background first. If you aren’t already familiar with Kurzweil, go Google him and browse around for a few minutes. He was the first to develop print-to-speech scanning technology (Stevie Wonder was his first customer), he’s the inventor of the Kurzweil Keyboard (here’s an interesting short video about the development of that technology with a brief mention of the upcoming role of AI in music), he’s spent his entire life in computers/high tech and he has a long track record of guessing correctly about upcoming technological advances. Not only is he deep in the AI world, he’s able to report back out to the rest of us what he sees on the horizon.

And now, back to the swearing.

Moore’s Law. Most are familiar with the concept as it’s one of the bedrocks of technological advancement over the past 60+ years. While not actually a law like the laws of physics, it’s the fact that computing power tends to double roughly every 18-months while holding costs steady. That means that in 2026, I should be able to purchase 2x the computing power than I can today with the same hit to my wallet. We’ve been on this doubling trajectory for long enough now that whole new vistas are opening up on the horizon of what it is to be human.

The first “Damn!” of the book: Kurzweil applies Moore’s law going back to the Big Bang. Up to this point in my life, I’d only considered Moore’s law as forward facing tool with a beginning point in the 20th century.

Consider this: About 10 billion years elapsed between the first atoms forming and the first molecules (on earth) becoming capable of self-replication. Then there was about another 2.9 billion year span between first life on earth and first multicellular life on earth. Another 500 million years slips by and animals start showing up. Add another 200 million years to the clock and mammals appear.

Looking at life as the ability/power to process information, there is a trend emerging of accelerating change. “Focusing on the brain, the length of time between the first development of primitive nerve nets and the emergence of the earliest centralized, tripartite brain was somewhere over 100 million years. The first basic neocortex didn’t appear for another 350 million to 400 million years, and it took another 200 million years or so for the modern human brain to evolve.” 200 million years for modern brain development vs. 100 years-ish to hook our modern brains up to a radically expanded brain. Hmm. Damn.

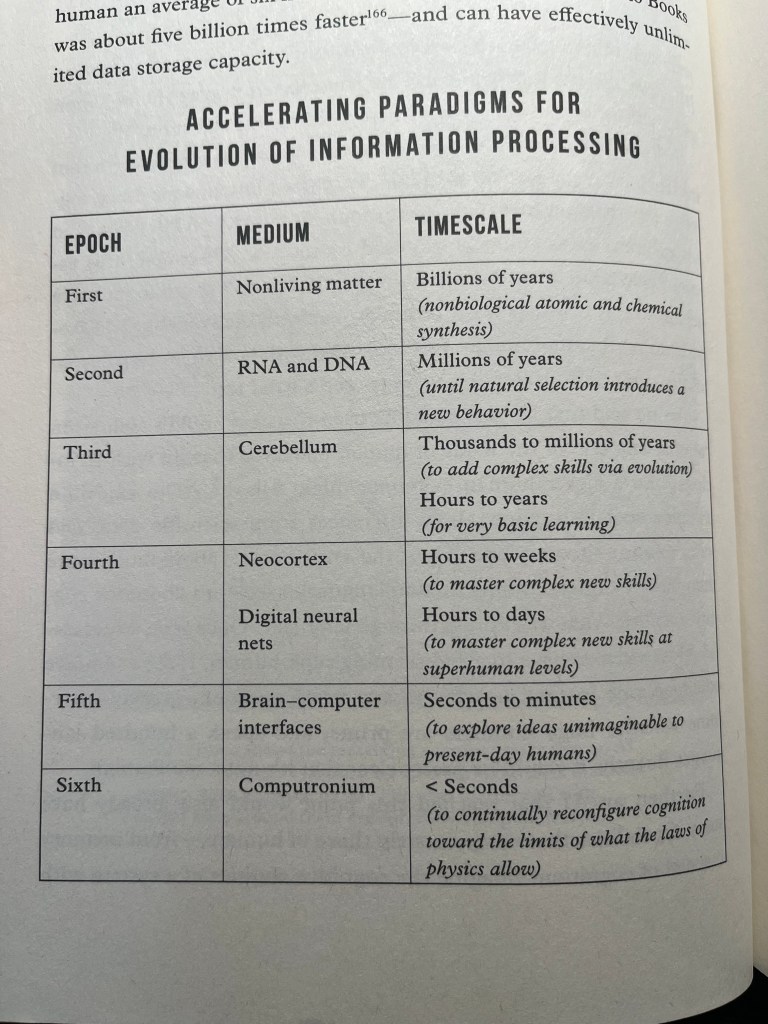

In a chart, here’s the progression of how long it takes us to process information and learn new stuff:

We humans here on earth are currently in the 4th Epoch. But we’re right at the cusp of slipping into the 5th Epoch. Articles with titles like “New brain-computer interface allows man with ALS to ‘speak’ again” are pretty commonplace these days.

So what happens when, according to Kurzweil’s prediction, humans are able to directly connect our neocortexes to the web? Daaaamn. At that point, who exactly am I? And with the ongoing exponential growth of computing power (with nano-scale computers projected to provide the computing power of 100 trillion human brains in the approximate volume of a single, current day human brain), the options become nearly boundless. Download the neuromuscular set of instructions for the ideal disc golf drive? Seems doable. Become a master music composer overnight? Why not? Holy damn.

Things are going to get weird in the coming decades. The pace of change we’ve seen over the past few generations is only going to accelerate. When I consider that my paternal grandfather was born in 1895 and lived a good chunk of his life basically in the Agricultural Age + Iron Age, I wonder what my [possible? eventual?] grandkids’ view on me will be.

Speaking of the Agricultural Age… Kurzweil spends a good amount of energy talking about the future of jobs and AI. Where are all of the current jobs going to go and what will replace them? In the 1890’s, over 40% of the American workforce was engaged in agriculture. We’re now sitting at 1%. Whether that has been a good thing for our society or not (Wendell Berry would take the adamant stance that it has not), the point remains that folks found jobs.

The other point is that even if agricultural workers in the 1940’s were told that their children, grand-children and great-grandchildren were going to become web site designers or digital video producers or Python or SQL experts, they wouldn’t have had a mental framework to make sense out of those words. Kurzweil’s argument with AI is that it is going to be such a radically different world that we can’t begin to explain to ourselves what it will look like.

Okay. I guess. But that’s not exactly comforting. Damn.

While it took 70+ years for ag jobs to drop from 53% of the workforce in 1860 to 21% in 1930, that was a relatively long timeframe. AI and massive computing power are poised to disrupt our current structures much more rapidly. What if, in the span of the next decade, nearly all trucking and delivery jobs were wiped away by autonomous driving? What if every radiologist were replaced over night by (better performing) AI tools? Bookkeepers? Fast food workers? My sense is that when cultural changes happen over the course of a generation or more, society has a chance to react. This time through the cycle, I’m not convinced that our social structures, regulatory systems, legal systems and safety nets are up to the task for the disruptions that Kurzweil lays out. Daaaaamn.

Speaking of social structures, our brave new future and who gets to enjoy (?) it, Kurzweil makes the assertion that a “kid today can access all of human knowledge with her mobile device.”

I think that’s a dangerous misstatement. And therein lies a significant flaw in Kurtzweil’s argument that AI’s benefits will be ubiquitous. As a business research librarian, I know that my library is spending upwards of $80,000 per year to provide “free” access to top-shelf business research tools and resources. The good stuff is not free. I don’t think it ever has been and I don’t anticipate it ever being so. No one is getting access to all of human knowledge on a mobile device without paying for the good stuff. So I guess that’s a good thing for libraries? Maybe? Hot damn!

As a framework for assessing any given technology’s societal benefit, I think it’s useful to ask who will have access to this technology? Who will be able to control the use of this technology? Will the control be primarily democratic or will it require bureaucratic, centralized organizations to manage it? Who will primarily benefit from the use of this technology? And mainly, who can afford it? On the plus side of the equation, I do think (despite the paragraph above), that access to AI will be relatively widespread. It’s not a technology like nuclear power that requires massive capital outlays or highly specific and specialized knowledge to make it hum. That’s the upside.

The downside is that AI will, in Kurzweil’s view, have the ability to custom design infectious diseases and create all sorts of mayhem. And… it will be in the hands of the average Joe. Damn. And daaaaamn.

But… before you despair too deeply, dear reader, here’s Kurzweil’s closing paragraph:

Overall, we should be cautiously optimistic. While AI is creating new technical threats, it will also radically enhance our ability to deal with those threats. As for abuse, since these methods will enhance our intelligence regardless of our values, they can be used for both promise and peril. We should thus work toward a world where the powers of AI are broadly distributed, so that its effects reflect the values of humanity as a whole.

Damn.